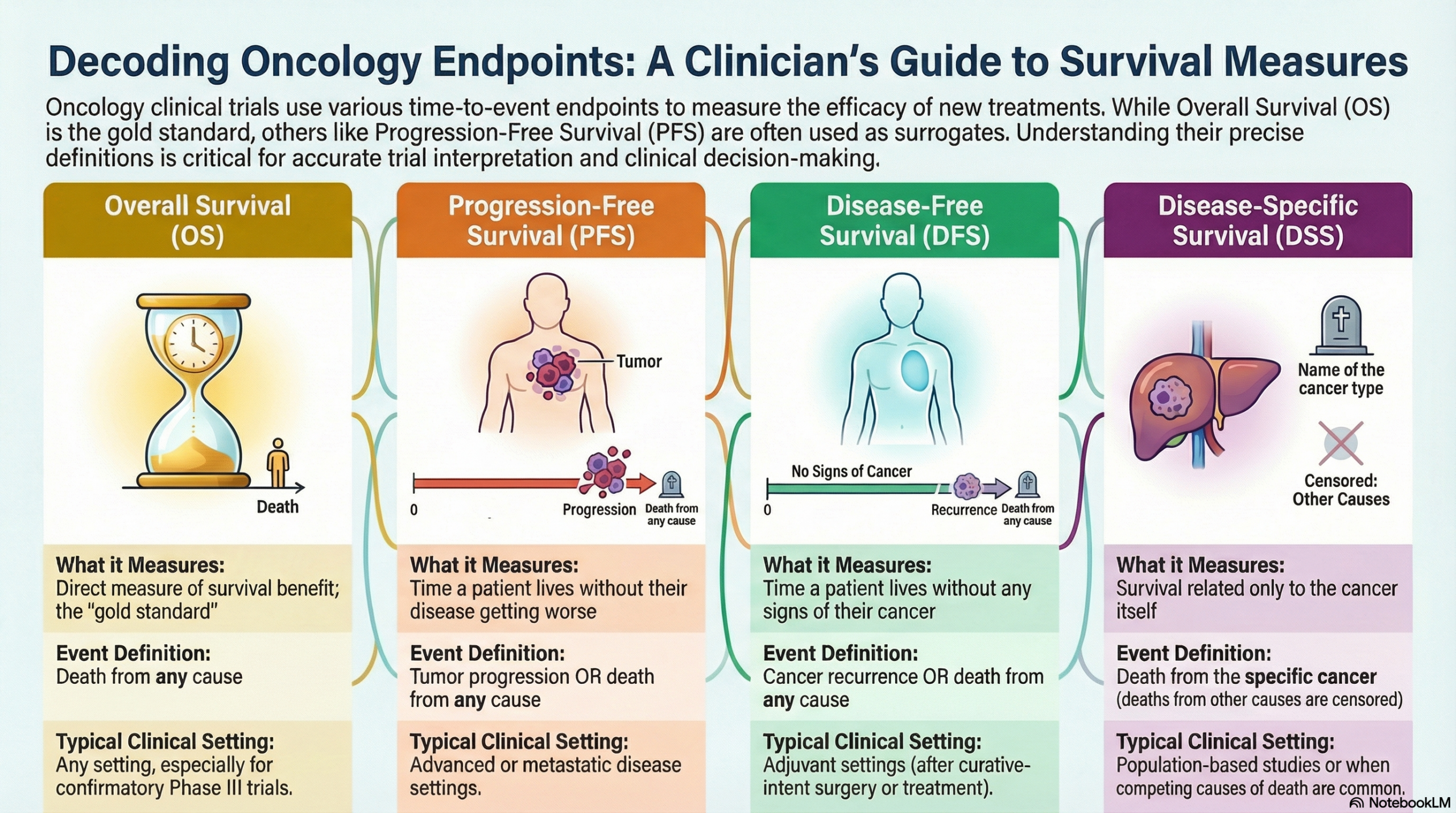

The following analysis differentiates Overall Survival (OS), Progression-Free Survival (PFS), Disease-Free Survival (DFS), and Disease-Specific Survival (DSS). These endpoints are distinct time-to-event metrics used to evaluate the efficacy of antineoplastic therapies.

The definitions and interpretations below are grounded in the FDA Guidance on Approaches to Assessment of Overall Survival in Oncology Clinical Trials and the RECIST 1.1 guidelines.

I. Overall Survival (OS)

Statistical Concept Definition

Overall Survival is defined as the time from randomization until death from any cause. It is a composite endpoint that treats death as the event of interest, regardless of whether the death was caused by the malignancy, treatment toxicity, or unrelated causes (e.g., cardiovascular accident).

Clinical Significance

OS is considered the “gold standard” endpoint in oncology. It is an objective, clinically meaningful endpoint that is precisely measurable. Demonstrating an improvement in OS is the most robust evidence of clinical benefit, particularly in diseases with short natural histories or late-line settings.

Descriptive Visual: The “Hard Stop”

Visualize OS as a simple binary timeline. The clock starts at randomization and stops only when the “system shuts down” (death). Imagine a survival curve where the line steps down only upon patient death. The cause of the shutdown does not alter the shape of the curve; it captures the net impact of the drug on the patient’s lifespan.

Critical Appraisal Guide

- Verify the Intent-to-Treat (ITT) population: The analysis should include all randomized participants.

- Check for Crossover: In randomized trials, if patients on the control arm are allowed to switch to the experimental drug upon progression (crossover), the OS benefit of the experimental drug may be diluted or confounded.

- Assess Follow-up: Ensure the trial follow-up was long enough to capture a sufficient number of events (deaths) to ensure the data is not immature.

Common Misinterpretations

Clinicians often assume that a drug showing tumor shrinkage (Response Rate) will automatically result in improved Overall Survival. However, discordant results are frequently observed where a drug demonstrates anti-tumor activity (PFS or Response Rate) but fails to improve, or even harms, OS due to toxicity.

II. Progression-Free Survival (PFS)

Statistical Concept Definition

PFS is the time from randomization until objective tumor progression or death, whichever occurs first. Progression is typically defined by radiological criteria, such as RECIST 1.1, which categorizes “Progressive Disease” (PD) as at least a 20% increase in the sum of diameters of target lesions (with a minimum 5mm absolute increase) or the appearance of new lesions.

Clinical Significance

PFS reflects the duration of tumor growth control. It is often used as a primary endpoint for Accelerated Approval because it is an “intermediate clinical endpoint” that can be measured earlier than OS. It is not confounded by subsequent lines of therapy, unlike OS.

Descriptive Visual: The “Growth Threshold”

Imagine a graph tracking the diameter of a tumor over time. There is a horizontal “threshold line” set at 20% growth above the tumor’s smallest recorded size (nadir). The PFS clock stops the moment the tumor size curve crosses that threshold line, or if the patient dies before that happens.

Critical Appraisal Guide

- Interval Censoring: Check the frequency of scans. If scans are infrequent (e.g., every 12 weeks), the exact time of progression is unknown, leading to interval censoring bias.

- Evaluation Bias: Determine if the progression assessment was subject to Independent Central Review (ICR). Because radiological assessment can be subjective, ICR protects against bias, especially in open-label trials.

Common Misinterpretations

A common error is equating a “statistically significant improvement in PFS” with “patients living longer.” A drug may delay progression by 3 months (statistically significant) but result in no difference in OS, or worse OS due to cumulative toxicity.

III. Disease-Free Survival (DFS)

Statistical Concept Definition

DFS is typically used in the adjuvant setting (after curative-intent surgery or radiation). It is defined as the time from randomization (usually at the time of no evidence of disease) until the recurrence of disease or death from any cause.

Clinical Significance

In settings where the tumor has been macroscopically removed (e.g., resected breast or colon cancer), there are no target lesions to measure for PFS. Therefore, the endpoint is the reappearance of the disease. Like PFS, it serves as a surrogate for OS but allows for faster trial completion.

Descriptive Visual: The “Remission Clock”

Imagine a patient starting with a “clean slate” (no visible tumor). The clock ticks while the slate remains clean. The clock stops the moment a new mark (recurrence) appears on the slate or the patient dies.

Critical Appraisal Guide

- Definition of Event: Scrutinize the protocol to see if second primary cancers (a new cancer in a different organ) are counted as DFS events or censored.

- Assessment Schedule: Similar to PFS, the timing of surveillance imaging dictates the accuracy of this endpoint.

Literature Case Study

While the provided texts focus heavily on advanced disease (OS/PFS), the RECIST guidelines note that endoscopy or laparoscopy may be used to confirm relapse in trials where recurrence following complete response or surgical resection is the endpoint.

IV. Disease-Specific Survival (DSS)

Statistical Concept Definition

DSS is the time from randomization to death attributed specifically to the cancer. Deaths from other causes (e.g., car accident, heart attack unrelated to treatment) are censored.

Clinical Significance

Theoretically, DSS attempts to isolate the drug’s effect on the cancer death rate. However, regulatory bodies often discourage its use as a primary endpoint because determining the exact cause of death can be subjective and unreliable.

Descriptive Visual: The “Filtered Timeline”

Imagine the OS timeline, but with a filter. If a patient dies, the adjudicator asks, “Did the cancer cause this?” If yes, the curve steps down. If no (e.g., the patient was hit by a bus), the patient is removed from the dataset at that moment (censored), but the survival curve does not drop.

Critical Appraisal Guide

- Attribution Bias: Look for how “cause of death” was determined. Was it by the treating physician (who might be biased toward their drug) or an independent committee?

- Competing Risks: FDA guidance explicitly states that all-cause mortality should be considered for the primary evaluation of survival rather than excluding specific causes. Attributing death solely to disease vs. toxicity is often impossible.

Common Misinterpretations

Researchers may prefer DSS to make their drug look better by “censoring out” deaths that might actually be related to treatment toxicity (e.g., a cardiac death caused by cardiotoxic chemotherapy). The FDA guidance emphasizes that toxicity deaths are part of the safety profile and should be captured in all-cause mortality (OS).

Summary Table

| Endpoint | Event Definition | Primary Utility | FDA Regulatory View |

|---|---|---|---|

| OS | Death from any cause. | Gold standard for benefit. | Preferred endpoint; required to rule out harm. |

| PFS | Tumor growth (>20%) or Death. | Measures tumor control. | Acceptable for Accelerated Approval. |

| DFS | Recurrence or Death. | Adjuvant (post-surgical) setting. | Surrogate for OS in adjuvant trials. |

| DSS | Death from cancer only. | Isolates cancer impact. | Discouraged due to subjectivity in cause of death. |